«Derrocar a Allende»: inédito documento prueba que EEUU ordenó «agresión hostil» contra Chile

El Archivo de Seguridad Nacional de Estados Unidos difundió documentos inéditos que revelan las estrategias de Washington para desestabilizar el gobierno socialista de Salvador Allende.

El documento detalla los métodos que se emplearon, incluyendo a funcionarios estadounidenses que colaborarían con otros gobiernos de la región –principalmente Brasil y Argentina–, para aunar esfuerzos contra Allende.

Para conseguir el propósito, se bloquearían silenciosamente los préstamos de los bancos multilaterales a Chile y se cancelarían los créditos y préstamos a la exportación de Estados Unidos.

En paralelo se reclutarían empresas estadounidenses para que se fueran de Chile y se manipularía el valor del mercado internacional de la principal exportación de nuestro país –el cobre– para dañar a la economía interna, publica el diario español El País.

En paralelo se le permitió a la CIA alistar planes de acción relacionados con la futura implementación de la estrategia.

“Si hay una forma de derrocar a Allende, mejor hazlo”, indicó Nixon en el encuentro, según el manuscrito de Helms, que forma parte de los documentos publicados durante las últimas horas.

El presidente Nixon lo había decidido: se adoptaría un programa de agresión hostil, pero de bajo perfil, para desestabilizar la capacidad de gobernar de Allende.

“Nuestra principal preocupación en Chile es la posibilidad de que (Allende) pueda consolidarse y la imagen proyectada al mundo será su éxito”, indicó Nixon al dar las instrucciones a su equipo de seguridad nacional.

“Seremos muy fríos y muy correctos, pero haciendo cosas que serán un verdadero mensaje para Allende y otros”, añadió el 37º presidente de EEUU.

“Si bien sabíamos bastante acerca de las maquinaciones del Gobierno de Nixon para impedir o desestabilizar al Gobierno de Allende, resulta sumamente importante contar con estos documentos, incluyendo notas manuscritas y transcripciones de conversaciones telefónicas”, dijo al respecto el historiador chileno-estadounidense Iván Jaksic al citado medio.

“Es sorprendente ver cómo lo que antes parecía ser especulación era más que cierto. La crudeza del lenguaje y las medidas que se proponen para presionar al Gobierno de Allende y mandar señales inequívocas a otros países son francamente escalofriantes”, añade el Premio Nacional de Historia 2020.

“Son las palabras del poder y, con estos documentos, no queda duda que detrás de cada palabra hay medidas concretas que tuvieron un impacto directo en la agonía que vivió nuestro país en esos años”, señala también Jaksic.

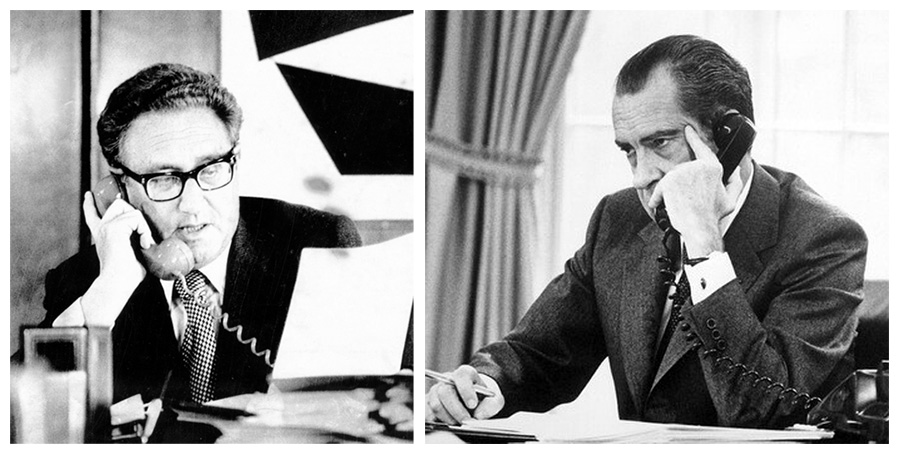

El rol de Kissinger

El asesor de Seguridad Nacional, Henry Kissinger, hizo gestiones de alto nivel para lograr reunirse a solas con Nixon antes de que lo hiciera el Consejo de Seguridad Nacional.

De acuerdo a un memorándum donde un funcionario del Gabinete del presidente justificaba el aplazamiento de la reunión, Kissinger había advertido: “Chile podría terminar siendo el peor fracaso de nuestra Administración: ‘nuestra Cuba’ en 1972”.

El encuentro entre Nixon y su asesor nacional de Seguridad se celebró finalmente en el Despacho Oval. Durante una hora, Kissinger presentó un estudio completo para que ganara el enfoque agresivo a largo plazo hacia el gobierno socialista de la Unidad Popular (UP).

“Su resolución sobre qué hacer al respecto puede ser la decisión de asuntos exteriores más histórica y difícil que tendrá que tomar este año”, advirtió a Nixon, dramáticamente.

“Lo que suceda en Chile durante los próximos seis a 12 meses tendrá ramificaciones que irán mucho más allá de las relaciones entre Estados Unidos y Chile”, subrayó.

Con todo, los nuevos documentos confirman lo que distintos funcionarios estadounidense han intentado negar por años: que la Casa Blanca tuvo responsabilidad directa en el quiebre democrático que sufrió nuestro país en 1973.

Aquella situación provocó nada más y nada menos que 17 años de una dictadura militar que encabezó Augusto Pinochet, quien terminó entregando el poder acorralado por el categórico triunfo del “NO” en el Plebiscito de 1988.

Allende and Chile: ‘Bring Him Down’

Several days after Salvador Allende’s history-changing November 3, 1970, inauguration, Richard Nixon convened his National Security Council for a formal meeting on what policy the U.S. should adopt toward Chile’s new Popular Unity government. Only a few officials who gathered in the White House Cabinet Room knew that, under Nixon’s orders, the CIA had covertly tried, and failed, to foment a preemptive military coup to prevent Allende from ever being inaugurated. The SECRET/SENSITIVE NSC memorandum of conversation revealed a consensus that Allende’s democratic election and his socialist agenda for substantive change in Chile threatened U.S. interests, but divergent views on what the U.S. could, and should do about it. “We can bring his downfall, perhaps, without being counterproductive,” suggested Secretary of State William Rogers, who opposed overt hostility and aggression toward Chile. “We have to do everything we can to hurt [Allende] and bring him down,” agreed the secretary of defense, Melvin Laird.

“Our main concern in Chile is the prospect that [Allende] can consolidate himself and the picture projected to the world will be his success,” President Nixon explained as he instructed his national security team to adopt a hostile, if low-profile, program of aggression to destabilize Allende’s ability to govern. “We’ll be very cool and very correct, but doing those things which will be a real message to Allende and others.”

Marking the 50th anniversary of Salvador Allende’s inauguration, the National Security Archive today posted a collection of documents that provide a detailed record of how and why President Nixon and his national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, established and pursued a policy of destabilization in Chile—operations that “created the conditions as best as possible,” as Kissinger later put it, for the September 11, 1973, military coup that brought General Augusto Pinochet to power. The detailed deliberations and decisions they contain clarify the misrepresentations by former policy actors over the years, Kissinger among them, of the true intent of the Nixon administration posture toward the Allende government. A half century after the inauguration, according to the Archive’s senior analyst on Chile, Peter Kornbluh, “these documents record the deliberate purpose of U.S. officials to undermine Salvador Allende’s ability to govern, and ‘bring him down’ so that he could not establish a successful, and attractive, model for structural change that other countries might emulate.”

When the CIA’s covert operations to undermine Allende were revealed on the front page of the New York Times in September 1974 by veteran investigative reporter Seymour Hersh they generated a major national and international scandal. The uproar over the clandestine U.S. role in Chile led to the first substantive congressional inquiry into U.S. covert operations, the first public hearings on CIA operations, and the first publication of a major case study, Covert Action in Chile, 1963-1973, written by the special Senate committee chaired by Senator Frank Church. “The nature and extent of the American role in the overthrow of a democratically elected Chilean government are matters for deep and continuing public concern,” Senator Church stated at the time. “This record must be set straight.”

But, asserting “executive privilege,” the administration of Gerald Ford withheld some of the dramatic documentation posted today from the Church Committee. As U.S. officials sought to falsify the purpose of U.S. intervention in Chile, Senate investigators did not have access to the complete historical record on the White House deliberations and decisions on Chile in the days before and after Allende’s inauguration.

The Official Narrative

In the immediate aftermath of the Hersh revelations, President Ford issued an unprecedented, if mendacious, acknowledgement of CIA covert operations. “The effort that was made in this case,” he told the press, “was to help assist the preservation of opposition newspapers and electronic media and to preserve opposition political parties.” U.S. intervention to preserve Chile’s democratic institutions was “in the best interests of the people of Chile and certainly in our best interests,” President Ford submitted as the Pinochet regime marked the first anniversary of what would become a 17-year military dictatorship.

In testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Henry Kissinger advanced this “preservation of democracy” rationale. “The intent of the United States was not to destabilize or to subvert [Allende] but to keep in being [opposition] political parties….Our concern was with the election of 1976 and not at all with a coup in 1973 about which we knew nothing and [with] which we had nothing to do.” Kissinger reiterated this argument in his memoirs, The White House Years.

Other former U.S. officials who participated in the anti-Allende operations also used their memoirs to re-write the history of U.S. intervention in Chile. In Good Hunting: An American Spymaster’s Story, published in 2014—and excerpted in the pages of the prestigious journal, Foreign Affairs under the title “What Really Happened in Chile”—the former CIA officer Jack Devine asserted that the CIA was merely “supporting Allende’s domestic political opponents and making sure Allende did not dismantle the institutions of democracy.” The goal, according to Devine, was to preserve those institutions until Chile’s 1976 election when those democratic forces, bolstered by covert U.S. support, would prevail over the evils of Allende’s Popular Unity coalition.

The “preservation of democracy” rationale made for good spin, but it is completely disproven by the declassified White House records. Those records reveal that the U.S. State Department, which feared an international scandal if U.S. efforts to overthrow Allende were exposed, argued for a prudent policy of co-existence—known as the “modus vivendi strategy”—while supporting the opposition parties and bolstering their chances of prevailing in the 1976 election. If Washington violated its own pronounced policy of “respect for the outcome of democratic elections,” the Bureau of Inter-American Affairs argued in one briefing paper during the internal debate over how to respond to Allende’s inauguration, it would “reduce our credibility around the world … increase nationalism directed against us,” and “be used by the Allende Government to consolidate its position with the Chilean people and to gain influence in the rest of the hemisphere.”

But the documents also reveal that Kissinger forcefully rejected that option, and personally convinced President Nixon to overrule it in favor of an effort to destabilize Allende’s ability to govern. “It is essential that you make it crystal clear where you stand on this issue,” Kissinger privately lobbied Nixon in preparation for the November 6 NSC meeting on Chile. “If all concerned do not understand that you want Allende opposed as strongly as we can, the result will be a steady drift toward the modus vivendi approach.”

Kissinger’s Arguments

The documents record that Kissinger was the prevailing influence for a sustained effort to destabilize and undermine Allende. As it became clear to him that the CIA’s efforts to foment a coup before Allende’s November 3 inauguration would likely fail, Kissinger presented Nixon with his initial arguments for a long-term aggressive approach that would be masked in its hostility. “Our capacity to engineer Allende’s overthrow quickly has been demonstrated to be sharply limited,” he wrote in a secret briefing paper on October 18, 1970:

The question, therefore, is whether we can take action—create pressures, exploit weaknesses, magnify obstacles—which at a minimum will either insure his failure or force him to modify his policies, and at a maximum might lead to situations where his collapse or overthrow later may be more feasible.

Kissinger posed two potential approaches for a hostile strategy:

—One would be a frankly overtly hostile policy, utilizing all possible pressures and demonstrating that hostility openly;

—The other would be a publicly “correct” but cold posture, with pressure and hostility supplied non-overtly and behind the scenes, and hostile measures demonstrated publicly only in reaction to provocation.

“Both courses” he submitted, “would use essentially the same measures—e.g., CIA activity, economic and diplomatic pressures. The difference—and the issue—lies in the question of how overt our hostility should be.”

As the National Security Council prepared to meet in early November, on October 29, Kissinger chaired a meeting of the Senior Review Group to determine what options on Chile would be presented for President Nixon’s final consideration. The Defense Department representatives advocated an overtly hostile approach; the State Department members cautioned against overt aggression, and pressed for a more flexible approach that held out the “option of establishing friendly relations with Allende in the event, now considered unlikely, that he moderates his Marxist and authoritarian objectives,” according to minutes of the meeting. The CIA, represented by Director Richard Helms, head of covert operations Thomas Karamessines, and the chief of Western Hemisphere operations, William Broe, supported a hostile approach, through covert operations, to undermine Allende. For security reasons, the covert action plan they drew up to destabilize Chile was classified as a special annex to the options papers and not distributed to the other agencies.

Assuring that the hostile approach prevailed was so important to Kissinger that he arranged for the NSC meeting to be postponed by a full day, so that he could get into the Oval Office for an hour to brief Nixon on how he should push the foreign policy bureaucracy toward a regime change posture. “Henry Kissinger came in this morning to try to see if we could move the NSC Meeting to Friday. He feels this is very important because the subject matter is Chile and Henry says it is imperative that the President study the issue prior to holding the meeting,” stated a memo to Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman from Nixon’s scheduler, explaining why the meeting was being moved from November 5 to November 6. “According to Henry, Chile could end up being the worst failure in our administration—’our Cuba’ by 1972.”

For his private meeting with Nixon, Kissinger drew up a comprehensive memo outlining “the serious threats to our interests and position in the hemisphere” and beyond that Allende represented—as well as the threat of the State Department’s position that the U.S. should adopt “a modus vivendi strategy” with an Allende government and focus on defeating him in the next election in 1976. The document, first published in Peter Kornbluh’s book, The Pinochet File, on the 40th anniversary of the coup, provides the most comprehensive explanation for U.S. intervention in Chile of any of the thousands of declassified records in the public domain.

“The election of Allende as President of Chile poses for us one of the most serious challenges ever faced in this hemisphere,” Kissinger wrote in his opening sentence, underlining it for effect. “Your decision as to what to do about it may be the most historic and difficult foreign affairs decision you will have to make this year,” he dramatically advised Nixon, “for what happens in Chile over the next six to twelve months will have ramifications that will go far beyond just US-Chilean relations.”

As reflected in the briefing paper, Kissinger’s key concern about Allende was that he had been freely elected, leaving the United States with little latitude to openly oppose his government as illegitimate, and setting a precedent that other nations might follow. Allende’s “model effect can be insidious,” Kissinger warned: “The example of a successful elected Marxist government in Chile would surely have an impact on—and even precedent value for—other parts of the world, especially in Italy; the imitative spread of similar phenomena elsewhere would in turn significantly affect the world balance and our own position in it.”

He lobbied Nixon to reject the State Department modus vivendi option, and instruct the National Security Council to implement a hostile policy to undermine Allende, but masked as benign diplomatic coolness toward his government. “The emphasis resulting from today’s meeting must be on opposing Allende and preventing his consolidating power and not on minimizing risks,” Kissinger advised Nixon.

At the NSC meeting the next day, Nixon parroted Kissinger’s talking points on the threat of the “model effect” that Allende represented. “We’ll be very cool and very correct, but doing those things which will be a real message to Allende and others,” he advised his national security team, according to the SECRET memorandum of conversation of the meeting. According to declassified notes taken CIA Director Helms at the meeting, the president also advised that “If there [is] any way to unseat A [llende], better do it.”

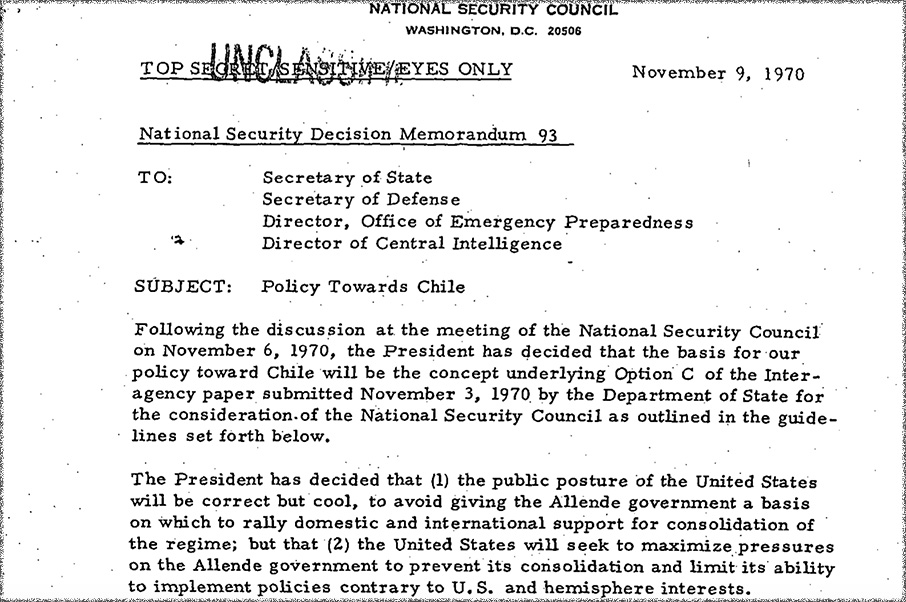

Six days after Salvador Allende’s inauguration, Kissinger distributed a TOP SECRET/SENSITIVE/EYES ONLY National Security Decision Memorandum titled “Policy Toward Chile” summarizing the guidelines from the NSC meeting. “The President has decided that (1) the public posture of the United States will be correct but cool, to avoid giving the Allende government a basis on which to rally domestic and international support for the consolidation of the regime; but that (2) the United States will seek to maximize pressures on the Allende government to prevent its consolidation and limit its ability to implement policies contrary to U.S. and hemispheric interests.” The directive authorized U.S. officials to collaborate with other governments in the region, notably Brazil and Argentina, to coordinate efforts against Allende; to quietly block multilateral bank loans to Chile and terminate U.S. export credits and loans; enlist U.S. corporations to leave Chile; and manipulate the international market value of Chile’s main export, copper, to further hurt the Chilean economy. The CIA was authorized to prepare related action plans for future implementation. The directive contained no mention of any effort to preserve Chile’s democratic institutions or to work toward Allende’s electoral defeat in 1976.

That same day, Kissinger called Nixon on the phone and they discussed Chile. Nixon had read Allende’s inaugural speech, as reported in the New York Times. “Helms has to get to these people,” Nixon told Kissinger, referring to covert operations in Chile. “We have made that clear,” Kissinger replied.

According to the declassified telephone transcript of their call, Nixon and his national security advisor then discussed their rationale for intervening against Allende. “I feel strongly this line is important regarding its effect on the people of the world,” Nixon stated, echoing the argument Kissinger had presented to him only four days earlier about Allende’s “model effect.” “If [Allende] can prove he can set up a Marxist anti-American policy, others will do the same thing.” Kissinger fully agreed. “It will have ______ effect even in Europe. Not only Latin America.”

Document 1

The White House, Memorandum for the President from Henry Kissinger, «NSC Meeting, November 6 – Chile,» SECRET, 05 November 1970

1970-11-05

Document 2

Director of Central Intelligence, «Briefing by Richard Helms, Director of Central Intelligence, for the National Security Council 6 November 1970, Chile,» SECRET, 05 November 1970

1970-11-05

Document 3

CIA notes, «The Director’s notes taken at 6 November 1970 NSC Meeting on Chile,» 6 November 1970

1970-11-06

Document 4

NSC, Memorandum of Conversation, «NSC Meeting – Chile (NSSM 97),» SECRET, 06 November 1970.

1970-11-06

Document 5

NSC National Security Decision Directive 93, «U.S. Policy Toward Chile,» TOP SECRET/SENSITIVE/EYES ONLY, 09 November 1970

1970-11-09

Document 6

NSC, Telcon, «President/Kissinger» [Conversation about Chile between President Nixon and Henry Kissinger], 09 November 1970.

1970-11-09

The CIA and Chile: Anatomy of an Assassination

On October 23, 1970, one day after armed thugs intercepted and mortally wounded the Chilean army commander-in-chief, General Rene Schneider, as he drove to work in Santiago, CIA Director Richard Helms convened his top aides to review the covert coup operations that had led to the attack. “[I]t was agreed that … a maximum effort has been achieved,” and that “the station has done excellent job of guiding Chileans to point today where a military solution is at least an option for them,” stated a Secret cable of commendation transmitted that day to the CIA station in Chile. “COS [Chief of Station] … and Station [deleted] are commended for accomplishing this under extremely difficult and delicate circumstances.”

At the State Department, officials had no idea that the CIA and the highest levels of the Nixon White House had backed the attack on Schneider—with pressure, weapons, and money—as a pretext for a military coup that would overturn the democratic election of Salvador Allende. They drafted a condolence letter for President Nixon to send. In a memo to National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, who was secretly supervising the CIA’s coup operations, the State Department recommended that Nixon convey the following message to the President of Chile: “Dear Mr. President: The shocking attempt on the life of General Schneider is a stain on the pages of contemporary history. I would like you to know of my sorrow that this repugnant event has occurred in your country….”

Marking the 50th anniversary of the U.S.-supported attack on General Schneider, the National Security Archive today is posting a collection of previously declassified records to commemorate this “repugnant event.” The Archive has also posted a CBS ’60 Minutes’ segment, “Schneider vs. Kissinger,” that drew on these documents to report on a “wrongful death” lawsuit filed in September 2001 by the Schneider family against Kissinger for his role in the assassination. The ’60 Minutes’ broadcast aired on September 9, 2001 and has not been publicly available since then. In preparation for the 50th anniversary, CBS News graciously posted the broadcast as a “60 Minutes Rewind” yesterday.

In Chile, the assassination of General Schneider remains the historical equivalent of the assassination of John F. Kennedy: a cruel and shocking political crime that shook the nation. In the United States, the murder of Schneider has become one of the most renowned case studies of CIA efforts to “neutralize” a foreign leader who stood in the way of U.S. objectives.

The CIA’s murderous covert operations to, as CIA officials suggested, “effect the removal of Schneider,” were first revealed in a 1975 Senate report on Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders. At the time, investigators for the special Senate committee led by Idaho Senator Frank Church were able to review the Top Secret CIA operational cables and memoranda relating to “Operation FUBELT”—the code name for CIA efforts, ordered by Nixon and supervised by Kissinger, to instigate a military coup that would begin with the kidnapping of Schneider. When the Church Committee published its dramatic report, however, almost none of the classified records were made public.

It took 25 more years before President Bill Clinton ordered the release of the CIA records on Operation FUBELT, as part of a massive declassification on Chile in the aftermath of General Augusto Pinochet’s arrest in London for human rights crimes. A close reading of the documentation exposes the false narrative that Kissinger, Richard Helms, and other high ranking officials presented to the Church Committee in their testimonies about their knowledge of, and responsibilities for, an act of political terrorism that led to the shooting of Schneider on October 22, 1970, and his death three days later.

General Schneider was targeted for his defense of Chile’s constitutional transfer of power. On May 8, 1970, he gave what the Defense Intelligence Agency described as an “outspoken” interview to Chile’s leading newspaper, El Mercurio, affirming that the Chilean armed forces would not interfere in the September 1970 election—a position that became known as “the Schneider Doctrine.”

As the commander-in-chief of the Chilean army and the highest-ranking military officer in Chile, Schneider’s policy of non-intervention created a major obstacle for CIA efforts to implement President Nixon’s orders to foment a coup that would prevent the recently elected Socialist, Salvador Allende, from being inaugurated. A “key to a coup,” as Chilean newspaper mogul, Agustin Edwards, told CIA Director Helms on September 15, 1970, in Washington, D.C. “would involve neutralizing Schneider” so other Army officers could take action. “General Schneider would have to be neutralized, by displacement if necessary,” U.S. Ambassador Edward Korry pointed out in a September 21, 1970, cable. “Anything we or the Station can do to effect the removal of Schneider?,” the CIA directors of Operation FUBELT queried their agents in Santiago on October 13.

THE SPONSORS

Kidnapping Schneider was the answer. By mid-October, the Defense attaché, Col. Paul Wimert, and CIA operatives known as “false flaggers”—agents flown in from abroad using false identities who were referred to as “sponsors” in the cable traffic—had held multiple meetings with Chilean military officers to discuss this operation. A coup plot beginning with the kidnapping of Schneider would accomplish multiple goals: remove the most powerful opponent of a military golpe; replace him with a military officer sympathetic to a coup; blame the kidnapping on Allende supporters; and create what the CIA referred to as “a coup climate” of upheaval to justify a military takeover.

Initially, the CIA focused on retired General Roberto Viaux as the officer most willing to move against Schneider. In secret meetings with the “false flaggers,” Viaux demanded an air-drop of armaments as well as insurance policies for his men. His CIA “sponsors” promised $250,000 to “keep Viaux movement financially lubricated,” while the CIA tried to coordinate his activities with other coup plotters. Active duty coup plotters were needed because Viaux commanded no troops; he was “a general without an army” who had the capacity to precipitate a coup—but not to successfully implement one.

On October 15, the CIA’s top official in charge of covert operations, Thomas Karamessines, met with Henry Kissinger and his military assistant, Alexander Haig, to update them on the status of coup plotting in Chile. They agreed that a failed coup would have “unfortunate repercussions, in Chile and internationally,” and “the Agency must get a message to Viaux warning him against any precipitate action” that would undermine chances for a successful coup later. According to the meeting minutes, Kissinger instructed the Agency to “continue keeping the pressure on every Allende weak spot in sight….”

The next day, CIA headquarters transmitted the conclusions of the Kissinger meeting “which are to be your operational guide,” to the Santiago station. “It is firm and continuing policy that Allende be overthrown by a coup,” the cable stated, preferably before October 24, when the Chilean Congress was due to ratify Allende’s electoral victory. “We are to continue to generate maximum pressure toward this end utilizing every appropriate resource.” The cable instructed the station chief, Henry Hecksher, to get a message to Viaux to “discourage him from acting alone,” and “encourage him to join forces with other coup planners so that they may act in concert either before or after 24 October.”

That message was delivered, and Viaux did as directed. He met with a pro-coup brigadier general, Camilo Valenzuela, and they coordinated a plan to abduct Schneider on October 19th, as he left a military “stag party” as the trigger for a coup. According to the plan, Schneider would be secretly flown to Argentina; the military would announce that he had “disappeared,” blaming Allende supporters who would then be arrested; President Eduardo Frei would be forced into exile, Congress dissolved, and a new military junta installed in power.

THE ASSASSINATION

The CIA was not only aware of this plan, they credited themselves for its development. “In recent weeks Station false flag officers have made a vigorous effort to contact, advise, and influence key members of the military in an attempt to rally support for a coup,” stated a Top Secret October 20, 1970, memo on the progress of “Track II,” as the coup plotting was designated. “Valenzuela’s announcement that the military is now prepared to move may be an indication of the effectiveness of this effort.”

Moreover, the Agency actively supported it. Using Col. Wimert as their primary interlocutor with Valenzuela and his top deputies, CIA operatives arranged to furnish them with untraceable grease guns, tear gas grenades, ammunition, and $50,000 in cash to finance the kidnapping operation. When the first attempt to kidnap Schneider on October 19 failed, as well as a second attempt the next day, the co-directors of the FUBELT task force, David Atlee Phillips and William Broe, instructed the station chief to “assure Valenzuela and others with whom he has been in contact that USG support for anti-Allende action continues.”

On the morning of October 22, 1970, Schneider’s chauffeured car was struck and stopped by a jeep as he drove to military headquarters. A hit team surrounded the car; as one member smashed the back window with sledgehammer, Schneider reached for his pistol and was shot at close range. He died of his wounds three days later.

Although CIA officials had discussed the potential for the abduction to turn violent, assassinating Schneider had not been part of the plan. Nevertheless, the CIA’s own post mortems on the operation showed no remorse. To the contrary, Agency officials firmly believed that the “die has been cast” for a coup to move forward. In his first report to Langley, the station chief, Henry Hecksher, cabled that “all we can say is that attempt against Schneider is affording armed forces one last opportunity to prevent Allende’s election….” At Langley headquarters, Richard Helms and his deputies congratulated the station on their “excellent job.” CIA analysts on the FUBELT task force predicted that the coup would now take place since the assassins would fear being prosecuted after Allende assumed office. The plotters would either “try and force Frei to resign or they can attempt to assassinate Allende,” a special report on the “Machine gun Assault on General Schneider” asserted. “Hence, they have no alternative but to move ahead,” another task force report suggested. “The state of emergency and the establishment of martial law have significantly improved the plotters position: a coup climate now prevails in Chile.”

The opposite was true. Repulsed by an act of political terrorism on the streets of Santiago, the Chilean public, the political elite and even General Carlos Prats who replaced Schneider as commander-in-chief, rallied to protect the constitutional processes which Schneider had defended. “The assassination of Army Commander in Chief Schneider has practically ended the possibility of any military action against Allende. It apparently has unified the armed forces behind acceptance and support of him as constitutional president in a way that few other developments could have done,” the CIA’s own analytical division, the Directorate of Intelligence, reported in the aftermath of Schneider’s death. On October 24, Allende was overwhelmingly ratified by the Chilean Congress. On November 3, he was inaugurated as the first freely elected Socialist leader in the world.

A COVER UP AND THE PURSUIT OF JUSTICE

In the aftermath of the assassination the CIA went to great lengths to cover up all evidence of its involvement with General Valenzuela, and to pay off General Viaux and his accomplices to stay silent. Colonel Wimert retrieved the weapons that had been sent—they were disposed of in the ocean—and the $50,000 that had been passed to Valenzuela. Although CIA officials testified before the Church Committee that they had no further contact with Viaux and his team after October 18, 1970, in fact they had multiple contacts as his representatives sought, in the ensuing months, $250,000 dollars to support the families of the men involved in the plot. Eventually, the CIA paid out $35,000 in hush money to representatives of the assassination team, according to a later CIA report submitted to the House Intelligence Committee, “in an effort to keep previous contact secret, maintain the good will of the group and for humanitarian reasons.”

For his part, Kissinger testified before the Church Committee that he had “turned off” coup plotting during the meeting with the CIA on October 15, 1970, and had never been informed that the plot involved kidnapping General Schneider. When the CIA records that appeared to contradict Kissinger’s dubious narrative were declassified during the Clinton administration, the National Security Archive’s Chile analyst Peter Kornbluh provided them to the Schneider family; they then used the documentation as evidence of complicity in a “wrongful death” civil lawsuit against Kissinger. «Recently declassified U.S. government documents and Congressional reports have provided Plaintiffs with the information, necessary to bring this action,” their legal petition stated. “The documents show that the knowing practical assistance and encouragement provided by the United States and the official and ultra vires acts of Henry Kissinger resulted in General Schneider’s summary execution, torture, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, arbitrary detention, assault and battery, negligence, intentional infliction of emotional distress, and wrongful death.»

According to the lawsuit, «the government documents show that, beginning in or about 1970, Defendants directed, controlled, committed, conspired to commit, assisted, encouraged, acted jointly to commit, aided and abetted, and/or were intimately aware of overt as well as covert activities to prevent Dr. Salvador Allende’s accession to the Chilean Presidency. These activities included the organization and instigation of a military coup d’etat in Chile that required the removal of General Rene Schneider, father of Plaintiffs Rene and Raul Schneider.”

Lawyers for the Schneider family filed the suit in District Court in Washington,D.C., on September 10, 2001. Eventually, the courts dismissed the case because Kissinger’s official acts as national security advisor to the president were protected from legal liability.

The Schneider case and the family’s lawsuit became the subject of a major ’60 Minutes’ investigation that was broadcast on September 9, 2001. Produced by Michael Gavshon and Solly Granatstein and reported by the late Bob Simon, the program examined the declassified record that exposed the White House and CIA complicity in Schneider’s murder. In an interview with the General’s son, Rene Schneider, Simon asked “does it make any sense” to pursue Kissinger, more than three decades after his father had been killed. “The truth is that I always wanted to put this behind me,” Schneider replied. “But we have a duty to humanity to speak out about this. It would be irresponsible to remain silent.”